Zero Irony

The Obligatory Heroes Post

I didn't want to like Heroes going into this season. It looked like yet another Smallville, a superhero show by people embarrassed to be doing a superhero show, so there wasn't going to be any costumes and it would trade more on Joseph Campbell's hero's journey and less on Jack Kirby's clobbering time. It certainly didn't didn't help that the pilot is pretentiously titled "Genesis" and the show seems to be based around a variation of the mutant gene. (as in, Mutant Gene, Why I Hate).

But it was the show on before Studio 60, which I was looking forward to (disappointingly), and I'm still as sucker for superheroes, so I tuned in to the pilot, where my low expectations were met. Except... it had that last minute twist that I honestly didn't see coming, and it had Hiro Nakamura, which made me just interested enough to catch the next episode, which made me just interested enough to catch the third, which kicked off with a moment that sealed the deal for me, but more on that later.

Heroes is a really good show. Like all great shows, Heroes greatest strength it its cast. They are across the board strong, which is impressive in a cast so large, with the noteworthy standouts of Hayden Panettiere (whom I've loved since she voiced Kairi in Kingdom Hearts) and Masi Oka.

Its second greatest strength is that the sucker moves. In a season where half a dozen shows warn their audience that there would be no resolution until May Sweeps, Heroes promises to set off a nuclear bomb in Mid-Town Manhattan in time for Veterans' Day.

And there's the cleverness with the powers. Lyle at Crocodile Caucus noticed that the badass powers, rage-powered superstrength and a hyper-healing factor bordering on immortality, belong to the women, while the men have more passive powers, telepathy, phasing, vague premonitions. The special effects are well done, especially for television and particularly the flights, which has plagued TV Supermen going back to George Reeves.

There are weaknesses. Some they've overcome: the pretentiousness of the pilot has been largely dropped or mollified. Some they haven't: both of the women have been sexually assaulted in only five episodes, and "Save the Cheerleader"? I mean, she's indestructible. Why not "Save the Emo Nurse with the MySpace Haircut?"

But I can ignore most of that because of Hiro Nakamura, the sensational character find of 2006 (sorry, Batwoman). He's easily the standout character of the show. He brings an energy to the show that drives the whole thing forward. The pilot is slow and ponderous, but the moment Hiro shouts "I DID IT!" in the middle of Times Square, with the camera orbiting him in a mad frenzy, the episode and the series comes roaring into life. (Followed up by "HERRO NEW YORK!" which is probably highly offensive, but I laughed anyway.)

A lot of critics think Hiro's appeal is that he's the fanboy made good, who knows his X-Men back issues and is excited (but not terribly surprised) to learn a future version of him exists and carries a sword. But that's not exactly it. We've seen that character before and usually, we hate him. See: Wesley Crusher (sorry, Wil Wheaton). Others say it's that he embraces his power, while the others are scared or ashamed. But Peter Petrelli embraces his power too, but I don't like him much*.

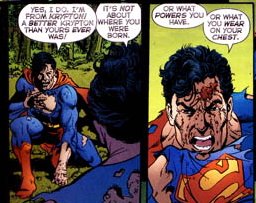

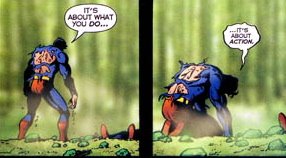

No, what makes Hiro a standout character is that he embraces being a superhero. Peter wants "to be somebody." Hiro wants to save lives. The moment for me, the moment I realized I was in, was the start of the third episode. Hiro's come back from his time traveling adventure, where he's discovered both the nuclear threat and a comic that can predict his future. But he has to cut short because "a little girls life depends on us". And he says this with ZERO IRONY.

Which is refreshing. There's just no way Buffy could have pulled off that line, or any superhero post-Adam West. It's just too spot on, too "this is what we do." But Hiro doesn't find saving lives absurd. Or even that heroic. He doesn't want praise for it, or recognition. He knows he has a power and with that power the responsibility to help people. He's already disappointed with himself for not being able to save everyone he could, and a close relative didn't need to get shot or nothing.

If the producers of Heroes were really brave, the pilot would have been just Hiro, and it would have followed his story for an hour from discovery of his powers through witnessing the bomb going off. Sure, it would have been mostly in Japanese and left a lot of the other characters in the wings, but it would have gotten most of the themes and even major plot points onto the table while hinting, with a newspaper headline here, an internet video clip there, a brainless dead body on the floor, at the other storylines. But mostly, it would have given Masi Oka more room to play. He really is delightful every time he uses his powers or asks himself "W W S-M D?" I'd be perfectly happy if the show was just about him.

And Hayden Panettiere. She's super cute.

*okay, I didn't like him much, until they revealed Peter doesn't really have a super power, he has other people's super power. It was a perfect power for Peter's personality, and made me particularly curious what happens when he finally meets Niki (and Niki's evil other half).