"What is this Hypertime that you speak of?"– Mark Waid at San Diego Comic-Con

Well, Mark, I'm glad you asked.

Hypertime was Mark Waid's [edit: Fine, FINE! and GOD OF ALL COMICS Grant Morrison's] attempt at replacing the parallel universe concept in the DC Comics universe.

Before 1986, most DC Comics were considered to take place in the same, "mainstream" universe and comics published by other comic book companies and even National comics published before the Silver Age were considered to take place in alternate dimensions, crossing over only through extraordinary measures. After 1986, that was changed so that ALL characters created for or acquired by DC Comics existed on the same Earth, which eased character interaction. (This, I consider, was a good thing, because crossovers are fun, create a richer history for the characters, and boost sales of the smaller titles through easier use of "guest stars.")

However, editorial mandate or not, DC Comics continued to publish books that did not take place officially in the DC Universe. Originally called "imaginary stories" and later branded as "Elseworlds," these stories took the familiar characters and either placed them in radically different settings or simply had events that would make an ongoing series difficult (such as, say, death). The most famous Elseworlds is Kingdom Come, by Mark Waid and Alex Ross, though The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen could be considered Elseworlds as well.

On top of that, there were film, television, print and radio versions of all these superheroes out there, with varying degrees of fidelity to the source material.

The "problem" was that these stories, despite being unofficial, had a habit tying into the main universe. Following the The Dark Knight Returns, the "main universe" Batman began acting more and more like the dystopian, aging, paranoid, sadistic version. Following Kingdom Come, Alex Ross's character re-designs started to appear in the main books, as well as hints that, in fact, Kingdom Come was the future of the DCU. And the Batman Animated Series introduced two important new characters to the Batman mythos (Renee Montoya and Harley Quinn), as well as changing (and improving) the design and origins for most of the characters (notably Mr. Freeze).

Hypertime was an attempt to address this reality. Mark Waid's [edit: and Bald and Beautiful Grant Morrison's] concept had two major differences from the previous theory of the Multiverse.

The first is that it included EVERYTHING. Every imaginary story, every Elseworlds, every movie, musical, every possible appearance by anyone anywhere. Presumably, this also included works that DIDN'T involve DC characters directly, like comics published by Marvel and Dark Horse. It certainly included comics published by Wildstorm, which DC Comics purchased the same year Hypertime was introduced. DC Editor Mike McAvennie once described it to me as "All stories are equally imaginary."

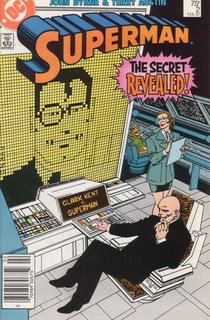

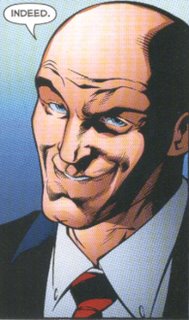

The second difference was that, rather than parallel Earths, the different worlds crisscrossed all the time, feeding into each other. So if, say, Smallville introduced a Lex Luthor who grew up in Smallville, yes, suddenly the DC Universe Lex Luthor had a childhood in Smallville as well. Under the old version, the Smallville Lex would have had to literally tear open a hole in the fabric of time and space and take the non-Smallville Luthor's place in order for that to occur. Under Hypertime, that changed history just sort of happens.

On the macroscale, it meant that any story, anywhere, COULD be an in continuity story for any one particular issue of, say, Impulse. Even if it's a fifty year old comic, or published by the Marvelous competition, or if it's a 19th century proto-horror novel. On the microscale, it means that every individual issue is a current within the main stream, which may or may not affect the other currents. After all, as Kurt Busiek once said, "they're all fairy tales we pretend take place in the same world because it's more fun that way."

BUT... as the quote above suggests, in the wake of Infinite Crisis, Hypertime is concepta-non-grata at DC Comics now. In fact, writer and editor alike act as if Hypertime has been, ha ha ha, erased from time. And the reason is... Hypertime never really worked. No one [edit: Not even 12th level intellects Mark Waid and Grant Morrison] ever did anything particularly interesting with Hypertime. Mostly, writers just treated it as another word for Multiverse, with the added bit that it might include some of our favorite Elseworlds characters (such as one AWESOME (and criminally uncollected) Superboy story).

Why was that? My theory is that Hypertime was too metaphysical a concept. Quite frankly, it was just a description of the way the creative process actually works. If he or she sees a good idea, consciously or unconsciously a writer will incorporate that idea into their work. Acknowledging, in story, that that happens may reduce fanboy whining about what is or is not in continuity (Yes, it's all in continuity), it doesn't actually help tell a better story. (At least not one that I can think of.) And so it's become passe.

Or has it? DC has, for now, stopped their Elseworlds line, though if New Frontier, JLA Classified, Bizarro Comics, Solo and the ALL-STAR line are any indication, they haven't stopped producing comics that are outside established DC continuity. They also still publish the Vertigo books, some of which still have an ill defined connection to the Justice League world, as well as Wildstorm's superhero and non-superhero books.

And despite the fact that Infinite Crisis ended three months ago, and DC has been publishing "New Earth" books for two months before that, we still don't know what the structure of the new DC universe is. We know that multiple Earths DID exist, it's been hinted that they still do, but it's also clear that Barry Allen, Jay Garrick, Billy Batson, Eel O'Brien, and Ted Kord were all born on the same earth, or at least everyone in the DCU remembers it that way. Similarly, the two page spread in Infinite Crisis #6 implied that EVERY comic DC ever produced, including the Zero Hour Legion and, ha ha ha, the Tangent Universe ARE also part of the New Earth, in some way. (My personal favorite part of Infinite Crisis #7 was the kids finding the Tangent Green Lantern on a beach).

So, was Hypertime really erased? Could it even be erased, considering it was just a description of the way comics were written anyway, an acknowledgment of the imaginary quality of the stories and the complexities of the world of ideas? Or have only our memories of Hypertime disappeared? For if GOOD ideas can cross from current to current, shouldn't BAD ideas be sluiced out, floating down the stream and getting lost in a sea of forgotten thoughts and half-formed dreams, never to be seen again?

Until, of course, one good writer has one good idea...

Second hardest character in fiction to write? A protagonist that's smarter than the you are. If someone is a certifiable genius, if, in fact, her super power is being a genius, then how are you ever going to come up with something so clever and wise that it earns the distinction of intelligence beyond the merely human.

Second hardest character in fiction to write? A protagonist that's smarter than the you are. If someone is a certifiable genius, if, in fact, her super power is being a genius, then how are you ever going to come up with something so clever and wise that it earns the distinction of intelligence beyond the merely human.

I'm watching the Dallas/Washington game and I notice that

I'm watching the Dallas/Washington game and I notice that