In my People's Superman post, I mentioned that Superman being an anti-aristocratic hero is an exception to the rule, that most superheroes are aristocratic in both background and behavior, and the best example of that is...

Batman.

Yes, Batman.

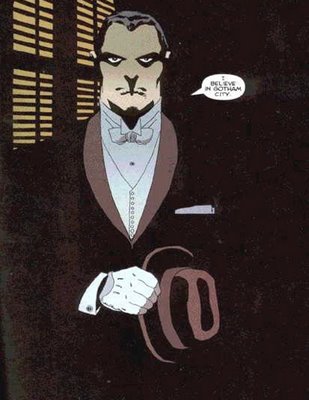

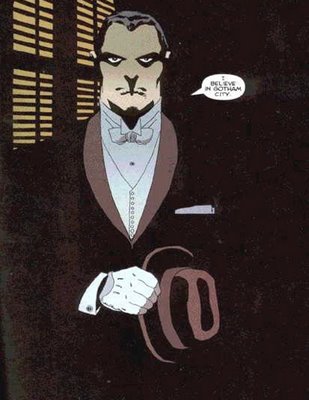

Batman isn't just "the man," Bruce Wayne is also The Man. He's a rich, white, handsome man who comes from an old money family and is the main employer in Gotham. He owns half the property in the city. In a very real sense, Gotham belongs to him, and he inherited all of it.

Batman isn't just "the man," Bruce Wayne is also The Man. He's a rich, white, handsome man who comes from an old money family and is the main employer in Gotham. He owns half the property in the city. In a very real sense, Gotham belongs to him, and he inherited all of it.

Accordingly, Batman has an enormous sense of entitlement. Batman just assumes he's right in every situation. It's his city. If he doesn't like you, he'll tell you to leave. If Batman thinks you're guilty of a crime, he'll put on his pointed white hood black mask and beat the crap out of you. Laws? Civil rights? Due process? Those are for other people. Yes, the people may have elected a mayor, pay taxes to employ the police. Batman could work with them, but they're all corrupt, weak, not as good as him. (Except Gordon. Batman has generously determined that Gordon is worthy to contacted, though he always disappears before Gordon's done talking, just to remind Gordon who's the bitch in this relationship.)

And look at who he fights! Superman fights intergalactic dictators, evil monopolists, generals, and dark gods. Batman fights psychotics, anarchists, mob bosses, the mentally frail, and environmentalists. Superman fights those who would impose their version of order on the world. Batman fights those who would unbalance the order he imposes on Gotham.

Consider the Penguin. He's a criminal, a thug. But what really distinguishes him is his pretensions to being upper class. The tux, the monocle. The fine wine and fine women. Running for mayor. He tries to insinuate himself with actual socialites, some of whom are attracted to his air of danger, but most of whom are repulsed by his "classless" manners. And when his envy and resentment of his "betters" turns to violence, Bruce steps in to teach him his place.

Consider the Penguin. He's a criminal, a thug. But what really distinguishes him is his pretensions to being upper class. The tux, the monocle. The fine wine and fine women. Running for mayor. He tries to insinuate himself with actual socialites, some of whom are attracted to his air of danger, but most of whom are repulsed by his "classless" manners. And when his envy and resentment of his "betters" turns to violence, Bruce steps in to teach him his place.

And it's not just Mr. Cobblepot. Hugo Strange, Black Mask, Facade, Catwoman, all villains from lower class backgrounds who want to be upper class, who want to hobnob with the rich and famous at one of Bruce's fabulous fetes, but just can't pull it off (well, Catwoman can, but Selina's in a class all by herself). Even Harvey Dent, before he became Two-Face, envied and resented his friend Bruce Wayne, because Wayne had money and Harvey had to work for everything he got. And then there's the villains who have a vendetta against C.E.O.'s of powerful corporations, either for revenge (Mr. Freeze, Clayface) or out of principle (Ra's al Ghul, Poison Ivy). There's a class war going on in Gotham, and Batman has taken the side of the rich.

Like Superman, there's an Arthurian "king-in-hiding" element to Batman's origin. "Banished" from Gotham by the death of his parents, Bruce Wayne returns to redeem his land and reclaim his throne. But instead of reclaiming it from usurping uncle or foreign invader, Batman must take Gotham back from a rising underclass.

And Batman doesn't even like the upper class he belongs to, either! Shallow, petty, boring, vain. They know nothing of the pain and suffering he sees every night when he hunts killers through the slums of Gotham, every day when he closes his eyes. He mockingly refers to himself as a "plutocrat" in last week's JLA: Classified, dismissing both value of plutocrats and the intelligence of a dictator who courts them. But does he dislike his wealthy peers because they don't appreciate how wealthy they are? Or is it because they aren't wealthy enough to appreciate how much responsibility he has?

And even if he thinks they're upper class twits, he really doesn't do anything about it. He leaves them in place, protects them from harm, flirts with and beds them. They're not the bad guys, after all. It's all those poor evil people. The one's who keep crashing the gate, who happened to be accidentally hurt in the hunt for profit. No reason Batman should try to protect them, keep them from getting crushed under the weight of capitalism.

They're just "penny-ante". And Bruce is a plutocrat!

She's there to contrast with Catwoman (Batman's match who is a woman), but she's such a strawman that nothing is really said. Maybe they should have used the female villain they've already established, Poison Ivy. Like Ivy, Catwoman is motivated by environmental concerns. Like Harvey Dent, Bruce Wayne throws himself into his relationship with Selina without much thought. However, Catwoman is entirely sincere in her beliefs, while Ivy destroys the plants she's trying to save to kill Batman. And Selina is mostly sane. When a company tries to buy the land she's trying to protect, Selina threatens to sue, to bring down every environmental group on them, and finds evidence that they're lying to the public. Poison Ivy, on the other hand, waits five years and then poisons the man who had the idea for the building, over a rosebush she's already saved. Catwoman would have been much better defined with a stronger character for contrast.

She's there to contrast with Catwoman (Batman's match who is a woman), but she's such a strawman that nothing is really said. Maybe they should have used the female villain they've already established, Poison Ivy. Like Ivy, Catwoman is motivated by environmental concerns. Like Harvey Dent, Bruce Wayne throws himself into his relationship with Selina without much thought. However, Catwoman is entirely sincere in her beliefs, while Ivy destroys the plants she's trying to save to kill Batman. And Selina is mostly sane. When a company tries to buy the land she's trying to protect, Selina threatens to sue, to bring down every environmental group on them, and finds evidence that they're lying to the public. Poison Ivy, on the other hand, waits five years and then poisons the man who had the idea for the building, over a rosebush she's already saved. Catwoman would have been much better defined with a stronger character for contrast.